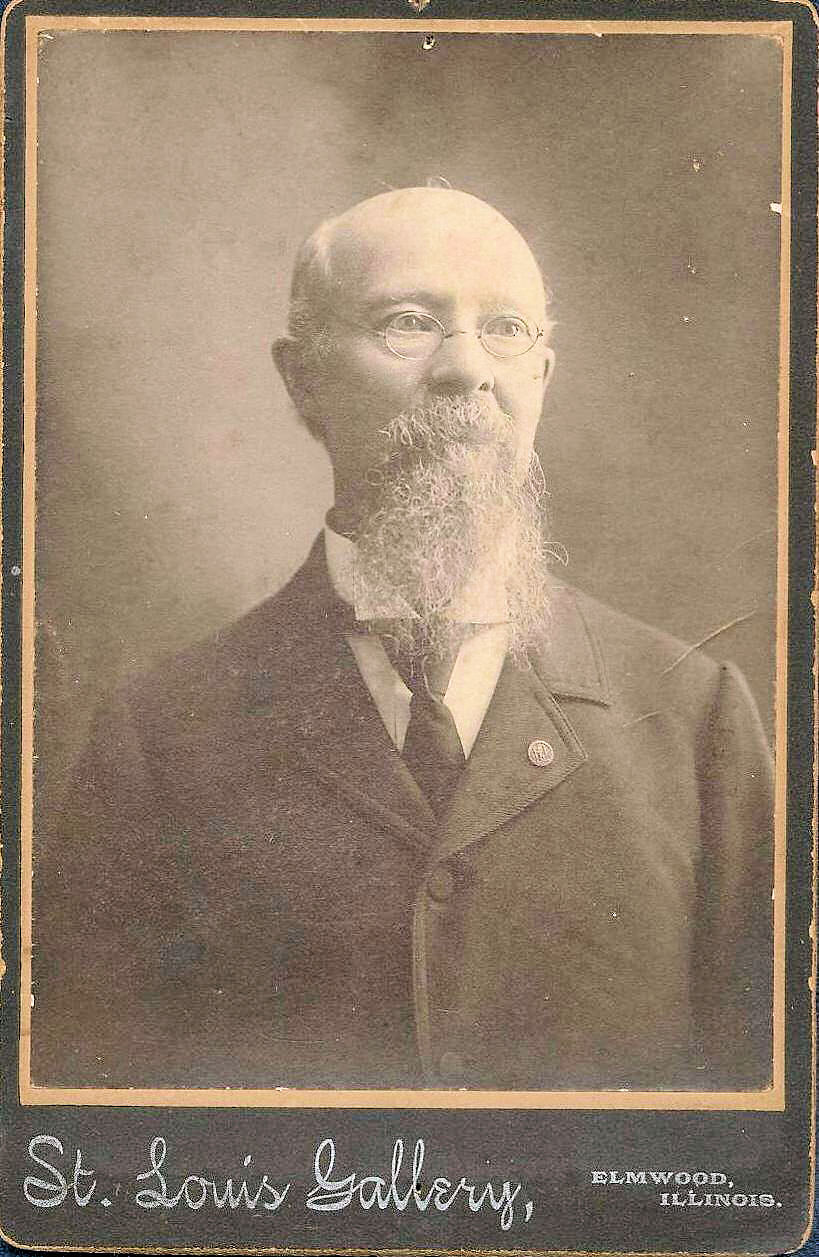

John Byers Reed

BIOGRAPHY - JOHN BYERS REED

By Robert Dale Reed

(Great-Grandson of John Byers Reed)

John Byers Reed was born to John Reed on February 23, 1831, in Wellsburg,

Brooke County, (West) Virginia. He was one of seven children of John Reed

and Margaret McMurray, the latter born in West Alexander, Washington County,

Pennsylvania, the daughter of Samuel McMurray, a native of Ireland.

They farmed land that was cleared by John Byers Reedís grandfather, Charles Reed,

a native of Scotland, and a prominent pioneer of Brooke County.

The seven children of John and Margaret were:

1. James, born February 23, 1820

2. Samuel, born December 1, 1821, in Ohio County, (West) Virginia

3. Mary, born abt 1823, wife of Joseph Gerry

4. Nancy, born abt 1828, wife of Hiram Elliott

5. Margaret, born abt 1829, wife of Thomas Hand

6. John Byers, born February 23, 1831, in Brooke County

7. Henry, born abt 1836

John Byers Reed farmed the land with his father, siblings, and grandfather

until he was 15. Then he left his home for a five-year apprenticeship as

a saddle and harness maker, in Triadelphia, Ohio County, (West) Virginia.

When he was 19, he left the panhandle of West Virginia, working three years

in Hancock County, Ohio, then a short while in Fort Wayne, Indiana;

before working in a saddle and harness shop in Brimfield, Illinois, in 1853.

His brother, Samuel Murray Reed, moved from West Virginia to

Millbrook Township, Peoria County, Ill. with his wife, Jane Davis Reed,

also in 1853. Samuel and his wife, Jane Davis, born in 1825, were

married in January 1852 in Ohio County. They had a son, Willis E. Reed,

born in 1853, and a daughter, Amanda Jane Reed, born in 1856.

Many of them are buried in French Grove Cemetery Millbrook Township,

Sec. 32.

John met and married Mary Darby on the 21st of December 1854 in Peoria,

Illinois; she was born in New York. Soon, a daughter was born but died

in childbirth. Another followed but died early in her life.

They moved to Elmwood in 1857 and had another daughter, Annie,

born February 4th of the same year; she lived. One more daughter,

Nettie, was born in 1859. By the census of 1860 the Reed family

found John Byers Reed a harness maker at 28, Mary at 23, Annie, 3, and Nettie, 1.

1861 was a cruel year for the Reeds: Annie died on January 15

at the age of 3 years, 11 months and 11 days. Soon after, death

struck again and took little Nettie. Depression filled the household

and then war came.

John Byers Reed, as many young men of Elmwood, Illinois, wanted in

on the fight for many reasons. Some wanted the flash of war and

to fight to save the Union. John Byers Reed wanted to join to get away from

the sorrows of Elmwood, but only one company from Peoria had been

accepted. A cloud of uneasiness and discontent formed over

the Peoria volunteers, wanting to get into fight before it was over,

to the point that many of them were willing to enlist in regiments

forming in other States. Finding an opening in the American Zouave

Regiment of Missouri forming at St. Louis, two Peoria companies

decided to join it. Afterward it became to be known as the

8th Missouri Volunteer Infantry (US).

(Click here for a

explanation of why people from other states joined the 8th Missouri)

On the 19th day of June, the Peoria Zouave Cadets, nearly a full company

of young men, left for St. Louis expecting to join that regiment

as a company, with Frank Peats as Captain. When they got to St. Louis,

Frank Peats and the volunteers were given a less then warm reception

and Frank Peats, declined the bid to become Captain. This had the

effect of disorganizing the Company for a time, and in the mayhem and

disgust half of the men went back to Illinois to join with other

Illinois Regiments yet to be created.

John Byers Reed went back to Elmwood, and he stayed one more month but

the grief of the loss of his daughters proved too great and

the diversion of war too strong. A group of 30 recruits calling

themselves the Pekin Zouaves from Pekin, Illinois, left Peoria for St. Louis,

to fill up the under-strength company on the 19th of June.

John signed his enlistment papers September 1st of 1861, joining

the 8th Missouri Infantry Regiment, Company H, as a private.

John caught up with the 8th Missouri Regiment in Cape Girardeau, Missouri,

and moved with the Regiment September 7th to Paducah, Kentucky and

stayed till February 1862. Then the 8th Missouri Infantry moved past

a snow-covered battlefield and captured Fort Henry, Tennessee on

February 5, 1862. The 8th Missouri aided in the capture of Fort

Donelson, on the Union right to retake the hill from which the first

brigade had lost that morning: Sunday February 16.

The capture of Fort Donelson produced elation throughout the North and

silence in the Confederacy. The Fortís surrender was the Northís first

major victory of the Civil War, opening the way into the heart Dixie and

preventing the Confederates from moving into Kentucky while making Grant

a hero to the Union. The Union losses at Fort Donelson were 500 killed,

2,108 wounded and 224 missing. Confederate losses were never estimated.

The 8th Missouri, with John Byers Reed, moved south along the Tennessee River

crossing the state of Tennessee into the Spring of 1862 and the battle of

Shiloh, April 6-7 1862.

Shiloh was

one of the bloodiest battles of the war, even though no ground was gained,

no strategic town was taken, no supply depot was sacked,

but the Union victory did force the evacuation of Confederate troops

from much of Tennessee and split the rebel forces along the lines formed

by the Mississippi River. With the battle of Shiloh behind them the

8th Missouri followed with the siege of Corinth, Mississippi, April 29th.

Then on May 17th, with Thomas on the right, drove back a strong rebel

outpost at the Russell House and captured high ground along the

headwaters of Phillips and Bridge Creeks. These new positions,

located within 4 miles of Corinth and only 2 miles outside Confederate

entrenched fortifications secured the victory. By June 3 the

8th Missouri started a long winding march to Memphis via Lagrange and

Holly Springs, Mississippi, and Moscow, Tennessee.

The food, the battles, the heat, cold and marches, took its toll on

every man. June 10th, unable to march any longer, John was

admitted to Mississippi Hospital debilitated from chronic diarrhea.

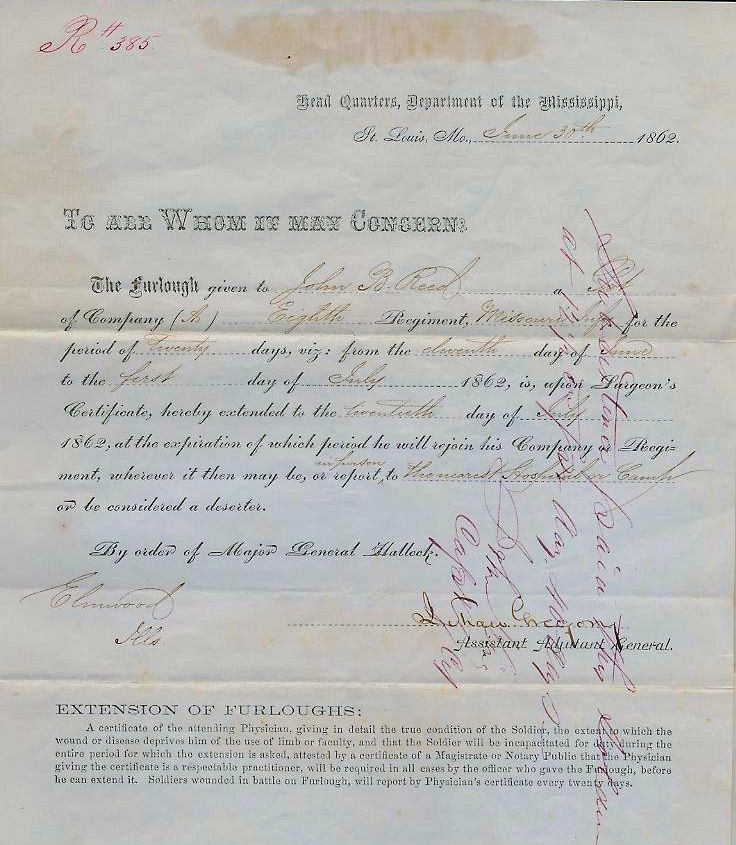

On June 11th, John received a furlough to the New House of Refuge Hospital

in St. Louis with transportation on a riverboat steaming up the

Mississippi, costing $3.24. There he was sent home to Elmwood

to recuperate and report back to St. Louis Hospital on August 6th 1862.

While convalescing in Elmwood, he found that a new cavalry unit was deploying

in Peoria in need of an experienced saddler. After reporting back to

St. Louis, John Byers Reed enlisted in the 14th Illinois Cavalry as a

saddler, September 20th 1862, putting his marching days behind him.

On January

7th 1863, John was promoted to Saddler Sergeant at the time of mustering.

The Saddler Sergeant in a Cavalry, North or South, receives orders

and instructions from the commander of the regiment. He is required

to repair the horse-equipment of the field staff of the regiment.

He instructs the company-saddlers how to do their work; and when

they are assembled to work in one shop, he acts as foreman.

He must keep a correct account of all the tools and material

entrusted to his care, and at all times be able to account for them.

In February and March 1863, the Regiment received its horses and equipment,

and was placed under thorough discipline and well drilled in tactics.

March 28, it started for the front.

April 17, the 14th Illinois arrived at Glasgow, Tennessee, being

headquarters there; the Regiment was almost constantly in the saddle

scouting. They pursued the rebel raider John Morgan from July 4,

until he was captured, the expedition covering 2,100 miles; they took part

in many of the skirmishes and battles on this raid and were especially

conspicuous at the battle of Buffington Island. During the night,

Morgan and about 400 men escaped encirclement by following a narrow

woods path. The rest of his force surrendered, after six days

pursuit thereafter, it then ended with capture of Morgan himself.

On the march, a cavalry could cover some thirty-five miles in an

eight-hour day under good conditions. However, some raids and

expeditions pushed man and beast to the limits.

Because of the hard use and endless riding John was keep busy with the

day-to-day repairs of both saddle and harness.

On the 14th of December, at Bean Station, the Cavalry alone had an

engagement, with the enemy's entire Corps attacking and then

losing 800 men. Here a Battery manned by men of the Fourteenth

did double service. The next day, the fight was renewed and the

enemy was again severely punished.

In many instances troopers fought dismounted, particularly in the later part

of the war when remounts became scarce, and the mounted cavalry charge was

looked upon as reckless. Some circumstances which called for

dismounting were: to seize and hold ground until infantry arrived, to

fill gaps in lines of battle, covering the retreat of infantry, fight

dismounted where the ground was impractical for mounted cavalry,

or as in the case at Bean Station man a field battery.

On July 30, 1864, in an encounter called "The Battle of Dunlap Hill," also

known as "The Stoneman Raid," Major General George Stoneman saw the

potential for strengthening Union forces by freeing men in two central

Georgia prison camps. He planned to take the city of Macon and free

the Union officers held at Camp Oglethorpe. Stoneman, with a well-armed

cavalry corps, of one been the 14th Ill. cavalry could then free the

officers imprisoned at Camp Oglethorpe in Macon and the many enlisted men

at Andersonville, about 45 miles further South.

Upon reaching Macon, Stoneman occupied the Dunlap House, set up temporary

entrenchments in the yard, and began to shell the city. Stoneman

didn't know that the city had advance warning of his arrival.

Johnston had brought together 2,500 boys, older men and convalescing

soldiers for Macon's defense.

On this raid, the First Battalion 14th Illinois cavalry was detached, leaving

the command, July 29, to make a flanking movement to destroy the chance

to be reinforced from the east and south by rail. In 60 hours,

night and day, it marched 160 miles, destroying 4 depots, 500 passenger

and freight cars, 40 engines, many miles of railroad track,

public buildings, and heavy military stores, many bridges, including the

great Oconee Bridge. Several times it marched near large bodies

of the enemy, at one time passing between the rebel picket and

Milledgeville, not over half a mile from the city, in which was a large

rebel force. It rejoined the Regiment August 1, in time to share

in the great disaster of the 3rd. After this raid, the scattered

fragments joined the line of battle in front of Atlanta, having the honor

to enter the city with our advance forces.

George Stoneman having failed in his goal to free 30,000 Federal prisoners

being held in Macon and retreated back to join Sherman when his cavalry

force ran into three cavalry brigades under Confederate Gen. Joe Wheeler.

The Confederates prevailed in the Battle of Sunshine Church, forcing

Stoneman to surrender. George Stoneman found himself imprisoned at Camp

Oglethorpe and his men were sent to Andersonville, the very prisons he

sought to liberate.

Colonel Capron, of the 14th Illinois cavalry, received permission to cut his

way out on hearing of Stoneman's capture. This he did, taking his

command with him, with success. August 3, at 1 o'clock in the morning,

Colonel Capron supposing he was beyond the reach of the enemy ordered a

halt. But a treacherous guide betrayed him and the men were attacked

about daylight. Being without sleep for seven days and nights many men

could not be aroused and every man was for him-self at this point.

In this condition many were killed or captured. Rebel soldiers,

guerrillas, citizens, and bloodhounds hunted those who were not captured

for days and weeks. The men that were able to escape came in singly

and in squads for weeks after. One party traveled over 400 miles

before reaching Union lines.

The only lasting effect of "The Stoneman Raid" on Macon occurred when a

Union cannonball, aimed at Confederate Treasurer William Butler Johnston's

home, struck the home of Judge Asa Holt. Today the Cannonball House

and the Johnston-Hay House attract visitors from all over the world.

Had the Stoneman Raid succeeded, the names of all connected with this raid

would have been as well known as the participants of the Alamo.

Due to its failure, it is all but forgotten outside of Macon.

September 15, the remainder of the 14th Illinois Regiment returned to

Kentucky, where it was remounted and re-equipped. After escaping

capture from the "Stoneman Raid", John Byers Reed was on furlough from

Lexington on the October 10th, to be back at Nashville on the 20th of

November.

When he got to Nashville, his 14th Regiment was battling Hood Forces in

Spring Hill, November 29, 1864.

When John rejoined the 14th, he retraced his tracks with his unit back

to Franklin on November 30 with Hood in pursuit, then again retracing his

tracks back to Nashville December 15-16. John witnessed the last

gasp of hope for Dixie in that battle of Nashville with Hood's forces

lacking the materials, troops, and supply lines to sustain a protracted

fight against an overwhelming force, in the dead of winter,

he must break off the battle.

The Battle of Nashville, including the pursuit to the Tennessee River,

capture and destruction of Hood's great army on Dec. 17th-28th,

practically closed the fighting and other aggressive work of the 14th

Regiment with the Brigade; it was afterwards stationed at Pulaski, Tenn.

While performing the ordinary camp and guard duties in Pulaski, the sorrow

of Elmwood reappeared when John heard of the death of his wife,

Mary Darby Reed, Feb 12, 1865. I am not sure what happened with

John at this time. I do not know if he went back home or if it was

too late for him to do so because of the snow and cold of February.

There are no records one way or the other, all I can tell you is, what

does not kill you only makes you stronger.

July 31, 1865: the 14th Regiment is mustered out at Nashville. John

went home to Elmwood.

Without considering the duty done by detachments, the main column of the

Fourteenth, during its term of service, marched over 10,000 miles.

The Regiment lost during service: 2 Officers and 23 Enlisted men killed and

mortally wounded, and 190 Enlisted men by disease. Total 215.

John picked up his life, and started his own harness shop in Elmwood

at the corner of Magnolia and Main, across from what is now a hardware

store. The building allowed him to live upstairs from the shop.

On November 8th 1866, John married Kezia Harlow, born in Sheffield, England

in 1842. She, with her mother and stepfather (surname Eggleston)

sailed to America in 1844. John and Kezia married in the neighboring county,

Knox, and quickly started a new family.

1868: Henry H. Reed, the first son, was born in Elmwood.

1869: John F. Reed, the second son, was born in Elmwood.

Our family has lost touch with these first two sons and what happened

to their families at this time.

1873: Charles E. Reed, the third son, my grandfather, was born in Elmwood.

When I was a

boy of five in the late 1950ís, I would find great fun in sitting out on the

front steps of our house, overlooking the Avenue and blowing a coronet

I had found, loudly at cars driving by to startle them. The people

would do a double take to see so much noise coming from such a small boy.

I would later find out this horn was Charles E. Reedís, and he would have

played it in Elmwood with the town band under the gazebo on Sunday evenings,

when he was a boy.

Charles E. Reed married Ethel Persinger on August 8th 1902 in Galveston,

Cass County, Indiana. She was born to Harrison Eli Persinger

(May 6th 1849-May 8th 1926) and Charlotte Louise Nana (1852-Nov. 25th 1942).

Harry Eli Persinger, son of Eli and Sophia Bleim Persinger,

was born in Logan County, Ohio.

Charles E. Reed and Ethel Reed moved to 595 Carroll Street, West St. Paul,

Minnesota, by 1902. They had two sons, John and Harry, the latter being my

father.

But with the new life comes loss in the death of the old man John Byers

Reedís father, John Sr., in 1882, Sand Hill,

Marshall County, West Virginia.

He was a farmer by occupation, and a worthy and respected citizen of

Ohio County, West Virginia, in which most of his eighty-five years were

spent. He is buried at Stone Church Cemetery, Wheeling, Ohio County,

West Virginia.

In Illinois, John Byers Reed was active with civic lodges of both

Brimfield and Elmwood. Arcaneus Lodge, No. 102, I.O.O.F., was first

instituted at Brimfield, Peoria County, Illinois, April 9, 1852, with

District Deputy G. M. Linneli in the chair. The charter, turned over

books and regalia to Grand Lodge Nov. 19, 1863. Re-organized under

the same charter in Elmwood, through the influence of Mr. John Byers Reed,

a former member of the Brimfield Lodge, July 7, 1873. The first

officers were Thomas. W. Keene, N. G., W. S. Ritchie, V. G., John Byers Reed,

Secretary, and Samuel Alluvelt, Treasurer.

The Soldiers' Union Association was organized in Elmwood, April 25, 1876.

This association and its members met yearly to decorate the fallen

soldiers' graves, John Byers Reed having been a charter member.

(Click here for a photo of the 8th MO Peoria area Reunion in the 1890's)

John Byers Reed died in 1913, and his grave is in the Elmwood Township

Cemetery. He left his wife and three sons, and a lot of good

stories; I wish I had heard them.

(Click here for information about the Elmwood Township Cemetery)

Sincerely -- ROBERT DALE REED, son of Harry Frances Reed, son of

Charles E. Reed, son of John Byers Reed.

A special thanks to Greg Maier for breaking through the wall of time,

and digging to get to the genealogy records of Johnís father and

grandfather. Also to Karen Hammer for all her work on the Peoria

County website. And to Linda Fluharty for her contributions to the

Wheeling Area Genealogical Society website. My Aunt Gladys Reed who

started me on this quest in 1979 with the gift of all the Reed family

photos. Also my Mother, Elsie Edna Bajari Reed and sister Vanessa

Reed Cowen for all the support.